PlumpJack!

IN THIS ISSUE: Cruciferous Weissman declares himself, corrective adventures in counting, and how the hell Bari Weiss and Clare de Boer might know each other

Appetizers

Stissing in Action

When news hit that Bari Weiss’s CBS News had signed on fresh talent, a certain name whetted our appetite: Clare de Boer. Yes, the once-queen of NYC’s King, now of the Hudson Valley’s Stissing House. There are of course surface-level questions: What exactly will she be doing? Does CBS even have food content? Will she attempt a Gabrielle Hamilton à la New York Times? But our epicurean minds have a much simpler query: How the hell do de Boer and Weiss know each other? Is there a right-leaning new media-fine dining cabal we’re wholly unaware of? (The answer, sadly, is almost certainly yes.) In the name of “Journalism” here’s a recipe Gourmet will be perfecting over time: a slop of pure conjecture served with a soupçon of reporting.

Four theories on the Weiss-de Boer connection:

- The first place to look is where adulting and class consciousness both begin: university. Weiss, as many are aware, attended Columbia. De Boer went to Brown. True, these are different institutions, but they are…in some views…Lesser Ivies. (I went to a no-name West Coast liberal arts college, folks! Just the messenger!) It’s tenuous, but it’s something.

- I once went to Stissing House (great meal!), and who was seated at the bar, clearly a regular? None other than Malcom Gladwell! If there was ever a person that could live betwixt these figures, it’s certainly Mac.

- Clare’s husband is a co-founder of the once-cool (?) mattress startup Casper. (I actually don’t have a fleshed out theory about how that could connect to Bari, I just wanted to share.)

- I texted a Friend in Fine Dining (a FiFD Element) to get their take, and ideally confirm my conspiratorial suspicions (on that note: if you also want to be a FiFD, email us! tips@gourmetmagazine.net). They had a much more logical explanation. “Only thought is that bari could be a reg at king,” they wrote. “Chefs usually stop by vip tables and chat. And i’ve had chefs become friends w them that way.” Huh.

If de Boer wants to weigh in, we’re all ears! —C.G.W.

Kales in Comparison

I am not named after the vegetable!!!! —C(ale).G.W.

Dept. of STEM

Were you able to spot the three times we abandoned our abaci and flubbed the math on our launch day? For those keen calculators paying attention yesterday, congrats! For the rest of us, the answers are below:

- We got excited about it being Gourmet’s semisesquicentennial. It is in fact the decennial of Gourmet’s semisesquicentennial (or quinctogintennial if you're into fake Latin).

- Our tier pricing was a little wonky: while we would love for you to subscribe at $10,000 a year, that is in fact not a 15% discount on $100 a month. That being said, if you’re inclined to give us ten Gs, you can do so in a tax-deductible way!

- The third math error is that we thought we made three math errors yesterday. There were only two. It was a big day.

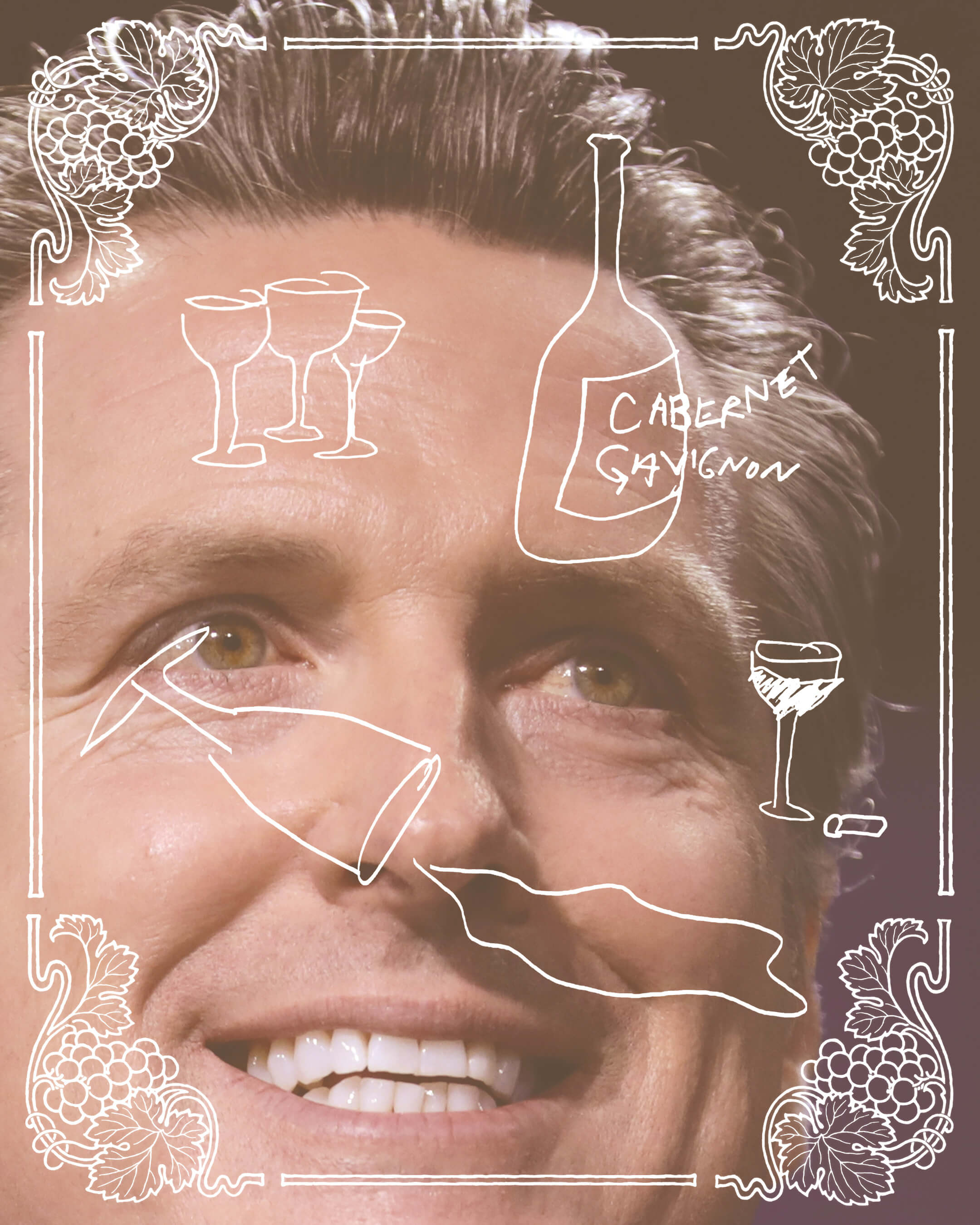

PlumpJack!

By Sam Dean

A journey through Gavin Newsom’s Napa wine empire, yielding visions of the future of wine and democracy.

It was a cool November day in San Francisco when I found myself among the BCBG brunch crowd of the Marina sipping an inky glass of Napa cabernet sauvignon—the 2021 Adaptation: dark tannins, dried herbs, red currant jam—to wash down an impeccably medium-rare burger on a broad baguette.

The burger was great; the wine was making my head swim. But whoever said hunger is the best sauce has never tried spooning the knowledge that they’re contributing to California Governor Gavin Newsom’s great personal wealth over their plate.

With each bite of this Balboa Burger ($21 with jack cheese), I was practically spitting nickels into his well-tailored pockets. The glass of cab ($23) was an even more concentrated contribution: Newsom is part owner of both the winery (Adaptation) and the restaurant (Balboa Café), which are both part of the larger PlumpJack Group.

To think that the mere act of dining out could help give Gav the financial freedom to tell his intern to capitalize the word FREEDOM in a new tweet, contribute funds to his 2028 presidential run, or even toss a few watts into the batteries of one of his many Teslas allowed me to not just eat, drink and be merry—I was being America, goddamnit, and chewing my way into the history of the greatest experiment in Democracy ever seen on the face of this planet.

Gav, the perpetually gelled and gravel-voiced 58-year-old governor of the Golden State, has become an anti-Trump national political celebrity in recent years, but it is seldom remarked that his career, before he even entered San Francisco city politics, rests on a foundation of restaurants, bars, wine shops, and fabulous Napa Valley wineries that he built and purchased alongside Gordon Getty, the opera- and wine-loving heir to California’s multibillion Getty Oil fortune.

These businesses, including the five Napa wineries of PlumpJack, CADE, Adaptation, 13th, and Odette, all of which produce cabs that have scored in the Robert Parker 90s and cost anywhere from $80 to $480 a bottle, live under the corporate umbrella of the PlumpJack Group. Newsom put his shares into a blind trust before being sworn in as governor in 2019, meaning he has no part in daily management; the group is currently run by his sister and his cousin. But his published tax filings show that the cash is still flowing: on his 2018 return, the last before he put the businesses in the blind trust, he reported earning nearly $800,000 from the companies that own and operate the wineries, more than half of his and his wife’s combined $1.5 million that year.

Newsom himself declined, through his office, to speak to me about his businesses of the vine, but I was determined to eat and drink (mostly drink) my way through his empire over the course of a whirlwind week in the Bay Area.

Why take on this heavy task? Because two of America's most treasured institutions hang in the balance: our semi-democratic political system and the California wine industry.

On the democracy front, you probably get it. Read the news, it’s not going great. Newsom is emerging as a possible presidential rival for the 2028 run against J.D. Vance (if not, somehow, Trump again), and these wineries, wine shops, and restaurants are, as Newsom himself told reporters when he decided to blind-trust them rather than sell them off, not only his major source of income but also “my babies, my life, my family.” If Trump is a man forged in the fires of flim-flam real estate deals, and Vance is a product of Yale Law and venture capital, then to understand Gav, one must understand PlumpJack.

On the wine front, you may not have heard: the industry is in crisis, mostly because demand is cratering. Growers are struggling to move juice, and unsold cases of bottled wine are piling up in winery caves and warehouses across the state. As a result, the 2025 California grape crush was the smallest it’s been in 25 years. Hundreds of thousands of tons of fruit were left rotting and unharvested in the fields, growers have ripped up or fallowed nearly 40,000 acres of vines, and everyone in the industry is operating under the assumption that the worst is yet to come. After a generational boom that saw wine drinking steadily grow from the 1980s through the early 2020s, every echelon of the industry, from the hot Central Valley flats of Lodi to the shimmering hills of Napa, has the sense that the party is over, or at least transitioning into a smaller, quieter kind of party.

The older generation of wine drinkers is dying, and the new one struggles to be born. Rob McMillan, the Silicon Valley Bank analyst whose industry forecasts appear each year with the thunder of prophecy, laid out the dismal terrain for me:

Boomers created this wine economy when they switched from liquor and beer to the fruit of the vine in the ‘70s, and McMillan credits a 1991 60 Minutes episode on “The French Paradox”—the paradox being the trim figures and healthy hearts of Parisians who down carafes de vin every single day—for convincing America it was a good idea to have a few more glasses now and then. Today, in his euphemism, the Boomers are “sunsetting” at a rapid pace (“It sounds nicer than ‘dying’”), and even the living ones just can’t drink like they used to.

Gen Z is lost in the thickets of vapes, hard seltzer, and total abstinence, the latter pushed by what McMillan calls the “neo-prohibitionists” who have fought back against the French Paradox paradigm with a wave of zero-alcohol propaganda. The last hope for the industry, in his telling, lies in the millennials, who are finally coming into their own as middle-aged high earners and are ripe for enticement by the sweet pipes of Dionysus into the dappled groves of wine-drunkenness. Enough of them have become wine-drinkers to support a national network of natural wine shops, drawn by esoteric terroir and the chuggability of glou, but that’s just a drop in the decanter—as a cohort, millennials aren’t pulling their weight like the Boomers used to.

If you squint through the blurred vision of many days drinking high-alcohol California reds, this all begins to feel like a mirror image of another Boomer-built, creaky, embattled libertine institution, one led by elites who insist that their taste is the taste of the masses, that an oaky chard, a fat cab, markets for everything and drone strikes abroad are what the people want. The fate of the Democratic Party of Newsom and the wine culture of the '90s are both uncertain; Napa Gav's lanky frame is woven through both.

A TRIM RECKONING

Gavin’s story began around the corner from Café Balboa, where San Francisco descends from the billionaire’s row of Pacific Heights into the flats of Cow Hollow and the Marina. In 1992, as a charming centrist Democratic governor ran his successful campaign for the White House (and Gav spent his early career watching and rewatching Bill Clinton speeches, practicing the pause, the thumb push, the lip curl, in front of a mirror, alone, per Tad Friend's 2018 profile), Newsom opened a wine store called PlumpJack.

That strange name, PlumpJack, reveals much.

It is, on its face, a sobriquet of Shakespeare’s John Falstaff, the perpetually wine-drunk and uproarious companion of the unhappy heir-apparent Hal in Henry IV, Part I. "Banish Plump Jack, and banish all the world,” Falstaff says to his prince, referring to himself in the third person. But Newsom, at age 25, did not choose the name just to pay homage to the bard, but to his patron.

Gav started the business with two business partners: Gordon Getty, son of the fantastically wealthy California oil magnate John Paul Getty and childhood friends with Gavin's dad Bill (himself a California state judge and manager of the Getty family fortune), and Billy Getty, Gordon's son and Gav's chum.

Gordon Getty, in turn, was and is a music nut—he’s personally paid for the upkeep of many of San Francisco’s musical institutions, and composed a number of operas over the course of his 92 years and counting, including, in the 1980s, an opera, Plump Jack, based on Falstaff. So when Gav and Billy were looking around for something to do with their lives, and Gordon agreed to stake them in a wine business, they took the name from his pet project. (It also, to my ear, evokes the see-sawing oilfield pump jacks that ultimately funded all these endeavors).

Gav’s telling of the PlumpJack origin story has a strong bouquet of bootstrap, omitting the petroleum notes of Getty wealth. As he said on the popular podcast of former Navy SEAL Shawn Ryan recently, he “started with nothing, got 13 investors, borrowed five grand from my dad—$7,500 each—just grinding, man.”

Within a few years of opening the retail PlumpJack, Gav and Billy opened PlumpJack Café nearby, a spot with a chic California Cuisine menu and a wine list with bottles priced at retail. They went in on Café Balboa a year after that, transforming the neighborhood institution into what the New York Times called in 1998 a “glittering nexus for Gen-X San Franciscans with social and political connections.” Danielle Steele’s son was among the co-investors. Newsom, recently appointed to a S.F. supervisor’s seat by mayor Willie Brown, told the Times that noblesse oblige played a part in the decision to spruce the spot up. “We’re standard-bearers,” Newsom said. Fifteen percent of profits, at the time, went to local charities (these days, every PlumpJack property contributes a cut of some products’ sales to the PlumpJack Foundation, the organization’s charitable wing).

The original PlumpJack Café closed its doors in the 2000s, but the restaurant group still operates a complex in the zone. On top of Café Balboa and the PlumpJack wine store, they also own a club called White Rabbit around the corner, which I have heard on good authority has a secret back room where vouched-for regulars can dip into stronger stuff before returning to the dance floor.

Balboa has recently become famous again for sparking the current espresso martini era—the bartender told me that their prebatched tap (cold brew, Stoli Vanilla, and coffee liqueur) makes $4 million in revenue each year, and on the day I bellied up to the bar the black gold was indeed flowing. (PlumpJack wouldn’t confirm the number when asked, but did say 20% of Balboa revenue flows from the espressotini. They’re launching a canned version soon.)

But one cannot be considered a true California aristocrat with holdings in Cow Hollow alone. Since 1995, PlumpJack has been assembling a diadem of crown jewels across the eastern flank of Napa Valley, along the most expensive stretch of agricultural land in the country. They also run a PlumpJack Inn up in Tahoe, but that was out of my range (and budget). Napa, however, was in reach.

A COMMODITY OF GOOD NAMES

The plan was to purchase the PlumpJack Passport, a $200 tasting tour across three wineries lasting around six hours, including a boxed lunch, and convince a friend to pull a little bit of a Napa Sideways with me, minus the infidelity and depression and pinot noir. The friends, however, all turned out to have real jobs, or families, etc., and ultimately bailed on the weekday excursion beginning at 10 a.m.

So I found myself alone on that chilly morning, saddling up my cherry-red rental electric Mustang-branded Mach-E SUV and driving up the Saint Helena Highway to the first stop of the tour, two hotel lobby bananas and a cup of hotel lobby coffee in my stomach, for some world-class breakfast wine.

As I tooled up the road, Gavin was on a Twitter (OK, fine, X) jag, bragging that a new law had prompted a cluster of productions from California’s other troubled industry, Hollywood, to move operations back into the state. He also wished Joe Biden a happy birthday; under a picture of the former president riding a bicycle, he wrote “Happy Birthday, President @JoeBiden! We miss having a president who has physical stamina — and a functioning brain.”

Have you been to Napa? I had not. It all seemed very expensive from afar, and I’d avoided it in the past in favor of its western cousin Sonoma, when visiting the Bay, or the Central Coast wine country closer to my former L.A. home.

Napa is very expensive. The hotels, the restaurants, the rents, the bottles (it’s hard to find a solid one under $50, well above even my special occasion bottle budget). Most of all the land. Vineyards in the prime bottomlands of the valley, where grow the grapes for cult wines like Ghost Horse (which sells cabs that clock in at $6,000 and $4,500 per bottle), Screaming Eagle (bottles in the $3,000s), and Harlan Estates (hovering in the $1,500s), can sell for as much as $1 million an acre. Up in the farther reaches, away from the most famous appellations, Michael Mondavi sold a 129-acre spread called Oso Vineyard to PlumpJack for $14.5 million in 2022. Nearly half of those acres burned to ash in a wildfire this past summer.

Napa is also very beautiful, a grand cru of the standard California glory. I could not resist repeatedly taking videos of the scenery while driving around: blue sky, green mountains on both sides, grapevines, their leaves a golden yellow against dark brown vines in November, surrounding at all times. If I were friends with a billionaire and they wanted to help me buy a spread up there, I too would say yes.

But there are signs of distress. In the center of a barren field, a mass of wet-black ripped-up vines had been bundled into a jagged ball the height of a man. Small controlled fires seemed to burn in the distance. Inside most wineries I passed, vintages of the past two years likely sat unsold, waiting for an absent clientele.

My first destination was the 13th Vineyard, an 82-acre spread up on Howell Mountain that PlumpJack bought in 2016 to expand its 62-acre holdings at CADE Estate Vineyard next door. I immediately got lost inside the winery building, a hulk of 19th-century brick and stone with elegant French farmhouse proportions, but eventually found my tasting host, the winery manager, who seemed as unsettled as I was that I was there entirely alone.

The grapes of the lofty heights of Howell are famous for their thick-skinned tightness, she explained, a response to the greater extremes of heat and cold at 1,600 feet and above the fog line. While maximalist valley cabs can edge into the open sweet fruitiness of Hawaiian Punch, up here, it’s more black tea and cranberry juice, chocolate and cigarettes.

We worked through some side-by-sides of the recent cabernet vintages: the wobbly structure from a year of record rains next to the concentration from the dry year that followed, all delicious if intense so early in the day. The reserve cab sauv was very good, as one might hope for a $399 bottle of wine. I was slightly stunned by the numerous small pours of wines clocking in over 15% before noon, so I will admit that I failed to ascertain any secrets of Newsom up on the mountain, but the experience did add a certain luminous glow to the view of the valley as I drove back down to my next station, where I determined to pry some truths loose.

When I arrived at Odette, a 45-acre spread nestled up against the foothills of the Stag’s Leap district on the valley’s east side, I found a livelier scene inside the chic tasting room, a cavernous space with a wall of windows looking out on the vines. It was graduation day for the harvest intern class, and the winemaker was toasting their hard work over by the bar.

I was seated alone at a two-top to inhale my boxed lunch of a roast beef sandwich (Napa’s food laws are very complicated; anything hot was verboten). As I ate—and subsequently began my tasting of chardonnays, petite sirahs, and cabernets from Odette and Adaptation—I got to talking with the winemaker and my tasting host.

GENTLEMEN OF THE SHADE

When I asked about Gav, everyone got a little cagey and repeated the same points: he’s not running the operation, he’s busy being governor, and he plays no favors with PlumpJack in particular or the Napa wine industry writ large, including with the lockdowns in 2020 that shuttered most of the wine hospitality biz.

These lockdowns, and Gavin’s great political blunder within them, tied him inexorably to Napa in the mind of the state and the nation. In November 2020, just a mile or so west of Odette, he stopped by the French Laundry in Yountville for the birthday party of a Sacramento lobbyist. Other diners caught him on camera, maskless and indoors. The caution level for Napa County was low at the time, but he had been preaching on TV that social distancing was the law of the land. It looked very bad—not only for the Covid-rule breaking, but also for the let them eat cake vibes of breaking them at the French Laundry, where a meal runs $390 before wine pairings.

His mea culpas for the error have been profuse and elaborate. “I despise me for the French Laundry,” he said on the Shawn Ryan podcast. “I went to this damn restaurant” which was “the biggest boneheaded damn decision I made,” and “I went to a damn birthday party and I paid the price and I own it,” and “I beat the shit out of myself for that,” he said. On the same podcast, he addressed the allegations that he is a fancy man with less humility: “I know people say oh, he’s a wine guy. Elitist. Well you know what? Fuck you.”

(Gavin’s picked up a curse-filled staccato way of talking, throwing “damns” in odd places and “motherfuckers” in as some extra seasoning, then switching thoughts mid-sentence, as if he’d been practicing the jagged cadences of Falstaff himself.)

People at Odette told me that they’d had to deal with some rambunctious protesters looking to fight with Gavin over the years, especially during the COVID lockdowns, and ramped up security a bit to deal with their disappointment on finding that he wasn’t bopping around the caves.

Gordon, however, is a frequent presence: April, who was walking me through the wines, said the 92-year-old was “heavily involved,” and came through every couple months to host a dinner for his friends in the San Francisco classical music scene, sometimes running through a blind tasting of his own wines, nailing each one every time. The wines were, again, quite enjoyable—the cabs were more open and fruity than the Howell Mountain glasses, plummy, rich and herbaceous, the chard was pleasantly inching towards the zingy body of a good Chablis, since the new winemaker had abandoned the butterball approach of yore, and the petite sirah pulled from the Adaptation fields before they burned up was a peppery delight.

All were firmly out of my price range (the estate cab at $194, the petite sirah at $66), though April made an interesting point: compared to the $500-and-up bottles of the estate wineries right next door to the PlumpJack vineyards, their bottles were practically a bargain, a democratic wine for people with $200 to blow. Affordability, after all, is the new thing in American politics.

As the legions of the ultrarich grow every year, joining Gavin in his baronial wealth bracket or Gordon in his royal heights, the price remains right enough for the right people. When I contacted PlumpJack corporate to ask how the business was doing, they sent back a statement from John Conover, the managing partner of the group, who said that while they’re “navigating a period of real change,” “wine sales remain strong across our properties.”

I was sad to cut Odette short—April was great company, and I was quickly developing a taste for more tasting pours—but I was due at my final stop, PlumpJack proper, the kernel and heart of the enterprise. While backing out of the Odette parking spot, a fender of the Mustang somehow found itself forcibly pressed into a slender but substantial tree that had appeared to my left. But it was a gorgeous day, with the sun coming out from behind the clouds now. PlumpJack was just a few miles away, and I had been fortified by my roast beef.

I again found myself entirely alone when I arrived at the PlumpJack complex, down the end of a long dirt road. For the first time that day, I felt like I was on a farm, not a nice hotel: the buildings were low to the ground, covered in vines, painted earthy greens and reds or left raw wood in the afternoon light. The place exuded a late-20th-century California funk: some things were curlicued, and the initials of the business, P.J.W., were monogrammed onto a Ren Faire shield by the door to the tasting room.

The man who met me fit the scene. Hawaiian shirt, big beard, big belly, a taciturn bacchus who while scrupulously polite seemed a little like he’d rather be taking a nap. The wines, too, called back to the salad days of the ‘90s. My tongue was zapped by now, but the chardonnay was back in butter churn, the cab was relaxed and fruity, the merlot a swirl of dark cherry with a touch of mint on the finish.

My guide told me of the almost alchemical precepts of winemaking, the 110-degree summer days in 2022 that melted the tannins like iron in a crucible, the softness that comes with time in the bottle, and the arcane rules for adding or removing water in the barrel. He also told me that I'd just missed a big group, and the weekend prior had been a madhouse, and he himself had been drawn into PlumpJack by the party days of yore.

This man told me he had been a PlumpJack drinker for years, ever since he and his friend, precociously interested in wine in their early 20s, drove to Napa from Reno in search of the good life. The first place they stopped to taste was a disaster. The staff, snobby toward the young tasters, treated them “like dirt,” he said, so when they left and looked at their map, the absurdly-named PlumpJack seemed a siren call. Once they found the place, they were welcomed with open arms. When they asked about shipping cases to Reno, a staffer said she had no idea of the legal niceties but would personally deliver a case the next time she went up to PlumpJack near Tahoe, if they wanted.

He was hooked, and when he came back again on a weekend he found a rager, “just a mass of people,” a party where people waited three deep at the bar to get a pour, shouting over the music played from CDs people scrounged out of their cars and popped into the shop stereo. PlumpJack was a scene, the place where Napa habitués would stop for one last long tasting before everything shut down at 3 p.m., a winery with a bucket of both matchbooks and condoms by the door.

If there is a charisma about Gavin, even as he’s rebuilt himself into the persona of a pugnacious policy guy ready to run down his enemies with a ratatat stream of facts and technicalities, it might be this, the feeling that he’s the type of dude whose party it might be fun to crash. An early San Francisco political opponent tried to score points by accusing him, without any evidence, of occasionally using cocaine—Newsom vigorously denied it, but it does not seem like a stretch that someone, somewhere nearby, sometimes, was cutting lines between the glasses of wine. (The wine, too, Newsom gave up for a stretch in the 2000s, after reports that he had become too regular a tippler of white wines in particular for public probity, but he picked it back up a few years later).

Trump the teetotaler has tapped the glamor of the 1980s, grinning like Gekko while enacting the hyperviolent fantasies of Predator abroad and RoboCop at home, reigning as the dark soft counterpoint to the real California action hero governor Schwarzenegger. Maybe Gavin can exude his own ‘90s glow, convey the soft pep of a Mentos ad, run a campaign that feels like he’s driving up in a doorless and sparkling white Jeep Wrangler on a pristine California day, calling out “Get in, losers, all of you losers across this nation, unscrew a bottle of this $200 wine, and let the wind blow back your hair just like mine, it’s nearly 3 in the afternoon and the party isn’t over, not yet, not on my watch.”

Back at the hotel, after night had fallen, I secreted a butter knife wrapped in a cloth napkin out to the electric car charging spot and used it to pop the maladjusted fender of the Mustang Mach-E back into place under the dim parking lot lights. The DoubleTree Inn produced its own vintage of Napa Valley cabernet sauvignon, and a bottle had been free upon check-in if I followed the hotel on Instagram and showed the proof to the front desk. I knew it was a mistake, and since the owner of this hotel had shown no ambition to the highest office in the land it was no surprise that this cab was no PlumpJack, but before falling asleep, I had another little glass, to toast the darkness outside: if sack and sugar be a fault, god help the wicked.

NEXT ISSUE: Enter the Gourmet Taste Kitchen™